“More and more, people are coming in with 100,000 miles on them; 200,000 miles now isn’t even unusual,” says Molla, vice president of the Automotive Service Association (ASA) after spending 15 years with ASE. “And for these customers that come in regularly, think of how many potential safety items you find each year.”

Imagine the danger if those customers didn’t regularly service their vehicles (and how many already don’t), Molla says, putting not only themselves but also those around them on the roads in danger.

It’s one of the main reasons the ASA has made government-mandated periodic motor vehicle inspection (PMVI) programs a key focal point for its mechanical division leadership team. It’s also why the organization co-hosted its second annual Vehicle Safety Inspection and Maintenance Forum in St. Louis on Dec. 2.

Along with the ASA-Midwest and the Alliance of Automotive Service Providers of Missouri, the ASA brought with it a panel of auto industry, law enforcement and government leaders to offer presentations and panel discussions on the topic in hopes of starting a revival to a once-flourishing government initiative.

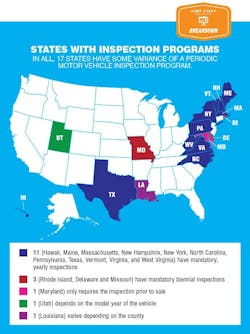

More than 30 states used to have full programs that required yearly inspections in every county.

That number is now 11.

The ASA’s goal: Reverse the declining number of programs, and, eventually, have PMVIs in all states nationwide.

“But the vast majority of shops know the importance of these, right?” Molla says. “That’s not who we need to convince. How do you convince consumers, lawmakers—all these people who will benefit? That’s the sticking point here.”

REAL PROOF

It’s difficult to prove a negative, Molla says. When vehicles do not crash, there are myriad factors: new technology-driven, in-vehicle safety features; road conditions; attentiveness of the drivers; etc.

“Do inspections play a role? Definitely they do,” he says. “How do you prove that with numbers and data and say, ‘This is why this program is necessary?’”

A June 2015 study from Carnegie Mellon examined the PMVI program in Pennsylvania, often lauded among the nation’s strongest. The study discovered that the fail rate among all lightduty vehicles was between 12 and 18 percent; a shockingly high number, far above the 2 percent benchmark the study said many cite.

That study only proves the cause in one state, though.

Often, the proof is more anecdotal. Take the ongoing Vermont court case in which an auto technician is being charged with a number crimes including manslaughter following the death of a customer whose vehicle was allegedly inspected improperly (“Vt. Manslaughter Case Serves as Industry Learning Opportunity,” November 2015). The ASA’s Washington, D.C. representative Bob Redding said at the time that the situation was a prime example of not only why these inspections are so necessary, but also how the process and system work effectively; a technician failed to follow statemandated protocol, a vehicle crashed as consequence, and now there appears to be tangible evidence that will likely lead to a penalty, he said.

A PLANNED SOLUTION

That’s an extreme case, though, and those speaking at December’s forum said more studies like the one in Pennsylvania are desperately needed. During one panel, Jade Winfree, a senior researcher for the U.S. Government Accountability Office, said that the majority of automotive administrators in states with inspection programs are confident of the benefits, but there needs to be more federal guidance, as well as collaboration and information-sharing between states.

The ASA is working on that, Molla says. The idea is to create a document of best practices between all the states with effective programs—how they are run, who is involved, how success/ failure is tracked, etc.

The ASA is currently in the information- gathering phase of the project and hopes to be able to put a document together this year.

“It can seem pretty complex at times,” he says. “And it’s an uphill battle to go to a state that doesn’t have one and pitch the need for this.”

“The hope is that we can take this document, go to anyone who might be considering it and say, ‘This is how it works, and it does work. You just have to follow this plan. It’ll make the roads safer, vehicles safer and consumers safer,’” he adds. “Consumers, lawmakers— none of these people see it every day like a [technician] does. We hope to show them.”